Decades before Anne Brontë picked up her pen to write The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (1848), the rugged hills of Haworth were already whispering a story of domestic defiance.

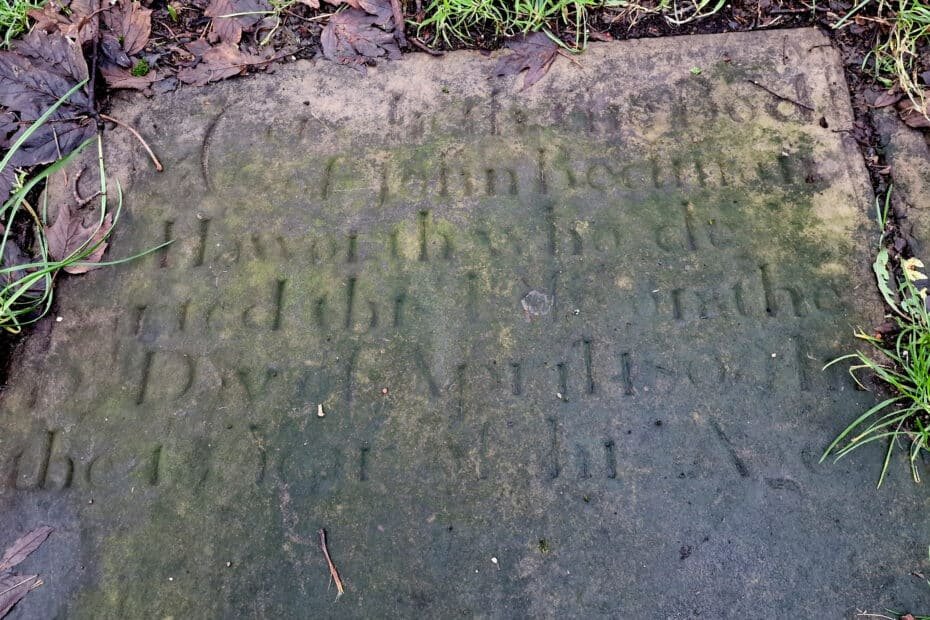

Recently, I started looking into the lives of the people buried in the graveyard of St Michael and All Angels. The stories told through epitaph, family trees and newspapers reveals startling and often stark pictures of the lives of the people who lived here.

One grave, dating from 1803, started an investigation that lead to two startling announcements from the Leeds Intelligencer in 1760, revealing that the plight of Helen Graham – the “mysterious tenant” who fled an abusive marriage – wasn’t just a Victorian provocation. It was a lived reality for local women long before the Brontës were even born.

The grave was that of one John Redman. But the conflict uncovered while researching the story was between his parents, John Redman Sr. and Judith Redman née Horsfall.

The Public War of Words: John vs. Judith Redman

In the mid-18th century, a woman’s legal identity was subsumed by her husband’s under the doctrine of coverture, which essentially “covered” a woman’s legal identity with her husband’s.. When a wife fled, a husband’s first move was often to “cut off her credit” via the local newspaper.

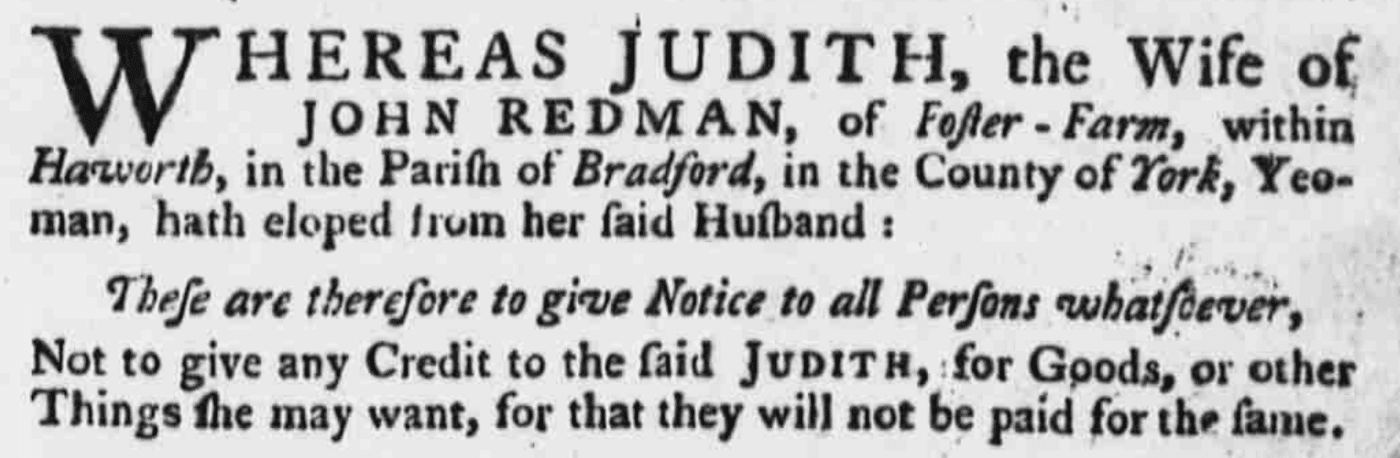

- July 29, 1760: John Redman of Foster Farm, Haworth, places a notice. He declares that Judith has “eloped” (the legal term for leaving a husband) and warns the public not to lend her money or sell her goods on his account. It is an attempt to starve her back into submission.

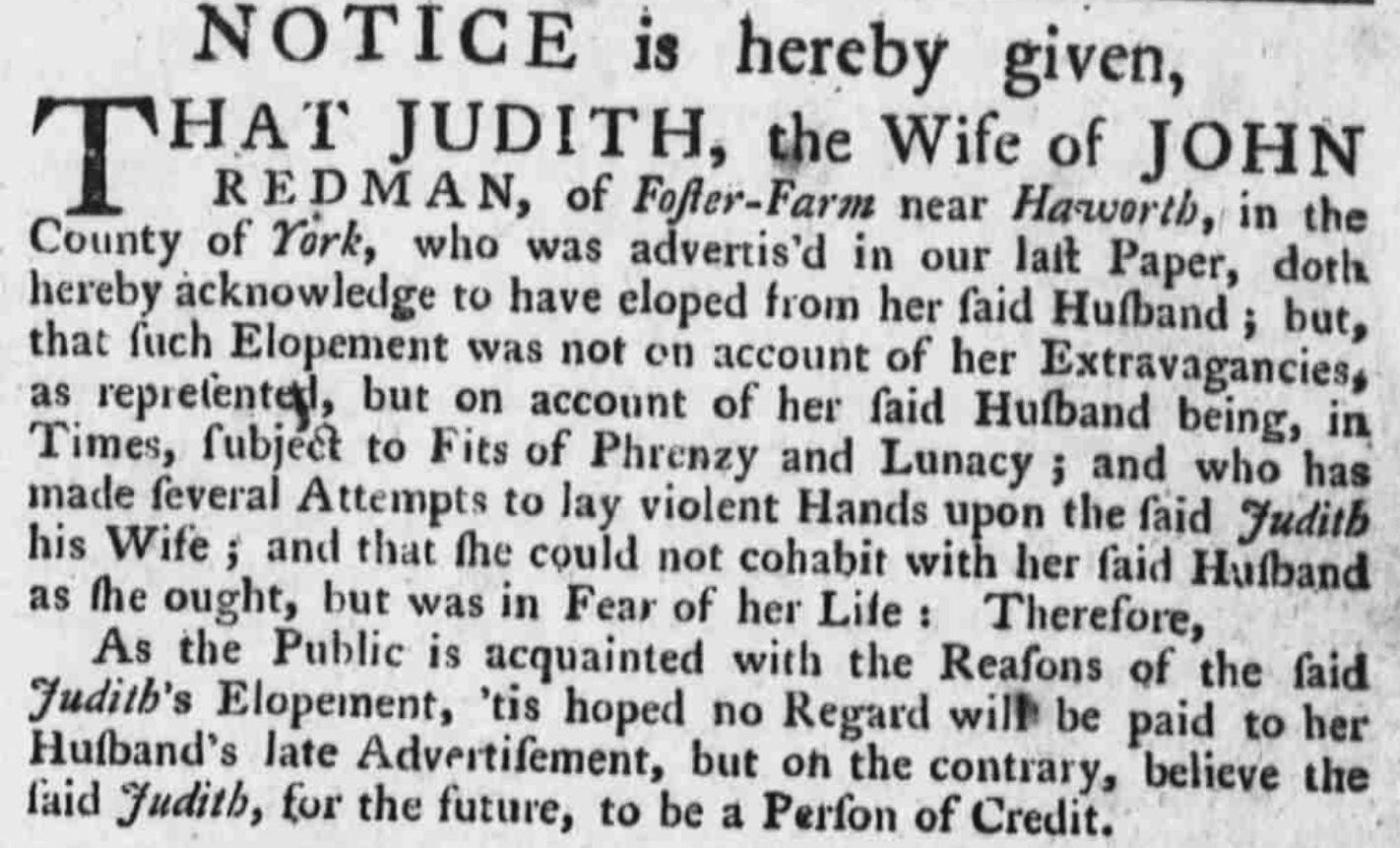

- August 19, 1760: Judith Redman does something extraordinary. She hits back. In a follow-up notice, she admits she fled, but corrects the record: she didn’t leave because of “extravagance,” but because John was subject to “fits of frenzy and lunacy” and had “made several attempts to lay violent hands upon” her.

Because a wife had no independent legal standing to own property or enter contracts, she relied on her husband’s credit for daily survival… a concept known as the “agency of necessity.” When a wife “eloped” (which in the 18th century often just meant leaving the marital home, not necessarily running away to marry someone else), the husband’s primary way to protect his finances was to publicly revoke that agency.

The “Elopement Notice”

Husbands would take out advertisements in local newspapers or the London Gazette to warn tradesmen. These notices typically followed a specific legal formula:

- The Proclamation: Stating that the wife (named by her maiden and married name) had “eloped from bed and board.”

- The Warning: Explicitly forbidding any person from “trusting or harboring” her on the husband’s account.

- The Disclaimer: Declaring that the husband would no longer be responsible for any debts she contracted from that date forward.

Why this was necessary

- Legal Liability: Under common law, a husband was legally required to provide “necessaries” (food, clothing, shelter) for his wife. If she bought these on credit, the shopkeeper could sue the husband for payment.

- The Adultery Loophole: If a husband could prove his wife had committed adultery or left without “just cause,” he was legally absolved of the duty to support her. The newspaper notice served as a public “line in the sand” to discourage shopkeepers from extending credit that the husband intended to contest in court.

- Reputation Management: These ads were often vindictive. By claiming a wife had “eloped,” a husband publicly branded her as an erring wife, which damaged her social standing and made it harder for her to find anyone willing to help her.

The Wife’s Rebuttal

Interestingly, the 1700s saw the rise of the “counter-advertisement.” Wives would sometimes pay for their own ads in the same newspapers to defend their reputations, claiming they hadn’t “eloped” but were forced out by cruelty, or pointing out that the “credit” the husband was protecting was actually based on a dowry he had already spent.

Foreshadowing the Tenant of Wildfell Hall

The parallels between Judith Redman’s defiance and Anne Brontë’s masterpiece are striking. Living in Haworth Parsonage, Anne would have been intimately familiar with the local history and the legal precariousness of women in the West Riding.

1. The Act of “Elopement”

In The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, Helen Graham’s flight from Arthur Huntingdon is a criminal act. By law, she is “stealing” herself and her son from her husband. Like Judith Redman, Helen has to live under a cloud of suspicion. When Judith asks the public to believe her “to be a person of credit,” she is fighting the same battle for reputation that Helen fights against the gossips of Linden-Car.

2. The Threat of “Violent Hands”

Judith’s claim that she was “in Fear of her Life” mirrors the claustrophobic dread Anne Brontë captures in Grassdale Manor. Arthur Huntingdon may not be “lunatic” in the 18th-century medical sense, but his alcoholic rages and psychological cruelty create the same environment of physical danger that forced Judith Redman to flee Foster Farm.

3. Financial Warfare

John Redman tried to use the Leeds Intelligencer to strip Judith of her ability to survive. Similarly, Arthur Huntingdon attempts to control Helen by limiting her resources. Helen’s secret, earning her own living as an artist, is her way of circumventing the very “denial of credit” that John Redman weaponised against his own wife.

“Thank heaven, I am free and safe at last! – Helen Graham, The Tenant of Wildfell Hall

4. To protect a child?

In Anne’s novel, Helen Graham was not just motivated by her own safety. She was also protecting her son. Not just from the abuse she knew Arthur was capable of, but she could not bear the thought of her son growing up to be like his father.

John Redman Sr. and Judith Horsfall married in 1758. Judith gave birth to a child in 1759 (Joseph Redman). She gave birth to John Redman Jr. in 1960, the same year as her elopement. While we do not as yet know if Judith eloped in 1960 taking her children with her, some circumstantial evidence points to that possibility. John Redman Jr. grew up, married and had three children… Mary, Joseph and Judith. That he named his son after his brother, and not his father, *and* named his second daughter after his mother, would certainly suggest that he maintained good relations with his mother.

Why It Matters

For years, critics slammed Anne Brontë for the “coarseness” and “unnatural” violence of her novel. Even her sister Charlotte felt the subject matter was a mistake.

However, these 1760 clippings prove that Anne wasn’t being melodramatic—she was being a realist. The story of a Haworth woman fleeing a violent husband and publicly defending her honor was part of the local DNA. Judith Redman’s brave rebuttal in the Leeds Intelligencer was an early, real-world draft of the scream for independence that Anne Brontë would eventually turn into a literary revolution.